Ejea

HISTORY OF EJEA

The history of Ejea de los Caballeros is that of an Aragonese town and that of a territory located at a crossroads through which many different cultures have passed. That is why its name has been adapted to the passage of time and its inhabitants: Sekia, Segia, Siya, Exea and, finally, Ejea de los Caballeros. Ejea, throughout the different periods of history, will become a coming and going of cultures, forming a rich and varied heritage.

PREHISTORY AND ANCIENT HISTORY

More than 10,000 years ago the environment that Ejea occupies today was populated by men and women who roamed the territories in search of resources that nature offered them to supply themselves. At first, they were nomadic groups that little by little settled in villages. New technical advances, as well as the introduction of agriculture and livestock in the Neolithic period, led to an economic revolution.

In Ejea de los Caballeros there are deposits from the Chalcolithic or Copper Age, with the appearance of remains of bell-shaped ceramics in “La Huesera”, “Cerro Vicario” or “La Valchica”. In this last deposit, 21 flat copper axes of very good quality were found. From the Bronze Age, the site of “Piagorri I” stands out, in La Marcuera, where different polished stone plates were found that would form part of a kind of arm`s doll for the protection of archers. There are also vestiges of other prehistoric times, such as the Iron Age.

Thanks to epigraphy and numismatics we know the existence of an Indo-European population in Ejea and its surroundings. Around 600 a. C., one of those towns, the Suessetanos, would be located in a large part of our territory, east of Navarra, and perhaps the Hoya de Huesca. Here they built the past Ejea, which these pre-Roman settlers called Sekia.

The Suessetanos had to succumb to the invasive impulse of the Romans around 184 BC. The Romans reoccupied the territory of Ejea, renaming it: now it was the Roman Segia. And they undertook an intense colonizing work. The Zaragoza-Pamplona road is included in the backbone of this process. The Romans took advantage of the innate conditions of Ejea for the cultivation of cereal and livestock, and extended a network of secondary roads that gave access to the villages and settlements of the population.

The presence of the Romans in what is now Ejea de los Caballeros is attested by the abundance of numerous archaeological remains: tombstones, ceramics, amphorae, sections of road, milestones such as that of Sora, dated in 9 BC. C., remains of street pavements in the La Corona neighborhood, everyday utensils such as vessels, plates and jugs, remains of kilns and pottery seals, a labyrinth-shaped graphite and hydraulic constructions, such as the Arasias weir .

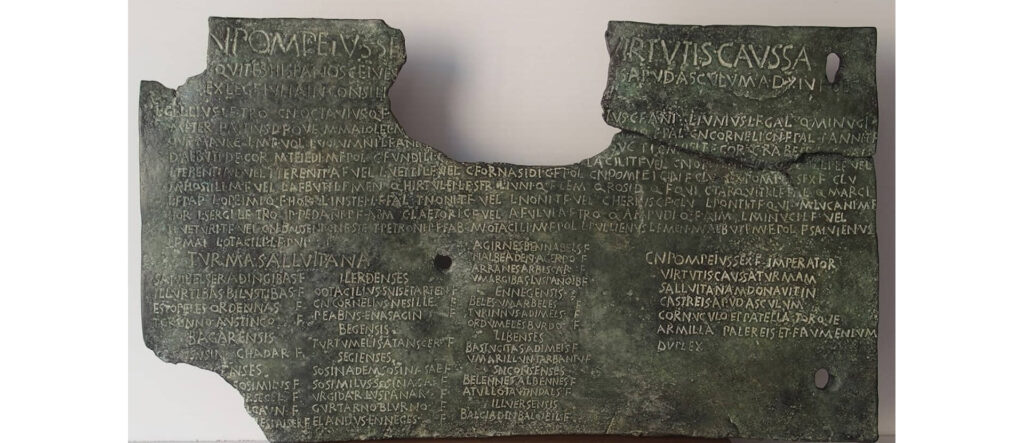

The courage of Segia’s settlers was reflected in an event that the Roman historians left a good note on. Sosinadem, Sosimilus, Urgidar, Gurtarno, Elandus, Agirnes, Nalbeaden, Arranes and Umargibas. These nine Segian warriors, the first Ejeans whose names we know, were part of the “Zaragozano Squad” that the Roman Empire recruited in foreign lands to fight in the Allied War in 88 BC. These early Ejeans demonstrated outstanding valor in the siege of the city of Ascoli. For this reason, in the year 89 BC, Rome distinguished them with the granting of Roman citizenship, being the first time that the Romans gave it to foreign warriors. Their names appear on the Ascoli Bronze, which is in the Capitoline Museum in Rome.

MIDDLE AGES

The Middle Ages is the time in which the Ejea appears configured, which will survive throughout time. The previous settlement now becomes a strategic point of the first order in the military strategy, first for the Muslims and then for the Aragonese kings. They founded a royal town, endowed with the privileges of freedom and self-government. Soon a prosperous economic enclave was developed, with an infanzona population jealously defending its prerogatives, and which will play a prominent role in the life of the Aragonese kingdom.

The fall of the Roman Empire meant a period of decline for Ejea. As of the year 545, its territory entered a process of demographic desertification and a decrease in the tone of socioeconomic life. The Ejea area came under the rule of a Spanish-Roman landowner, Count Casio. His power ranged from lands of Ejea to neighboring Tudela, in what is now the Ribera de Navarra. It was a vast territory in which cereal exploitation and livestock were the main economic activities.

The Muslims reached the limits of Ejea in 714, only three years after their landing on the Iberian Peninsula. They found a disunited and weak country, so they didn’t find much opposition from those who already lived here. As for Ejea, the Muslims came across an area dominated by Count Cassius. Applying a policy of non-violent conversion, Muslims they reached a pact with the Count: he and his family converted to Islam, keeping all their possessions, but paying homage to the new installed power. In this way, the Muladi dynasty of the BanuQasi was born, which always tried to achieve political primacy and the independence of the Omayyad Cordoba, even if for this they had to betray their new Muslim brothers and make a pact with the Christians.

The most important population center in the area was Ejea. The Muslims, like the Romans before, changed the name again: now it was to be called Siya. The Muslim Siya occupied urban planning part of what is now the La Corona neighborhood, the highest and best defensible place. The Muslims conceived of Siya as a strategic military location to control the Christian kingdoms and the Aragonese counties of the north. For this reason, most of the Muslims who arrived here were military and relatives of these. The rest of the population was autochthonous, Hispano-Romans who would become Mozarabs.

In La Corona, the Muslims built the zuda -the defensive fortress-, the mosques, the hamlet and a walled enclosure. Outside of it, towards the south looking at the Arba river of Luesia, the Mozarabic neighborhood was located where the few Hispano-Roman population that remained in Ejea settled, all of them of Christian religion. The Muslims allowed them to preserve their traditions and culture, as long as they paid the established taxes. In a secluded area to the north, where the Las Eras neighborhood is located today, was the Muslim cemetery.

The Muslims developed their economic activity in agriculture, making the most of the possibilities of irrigation. They extended the irrigation ditch system in the areas parallel to the Arbas rivers, in the Bañera area next to the Arba de Luesia and in what is now known as the Huerta Vieja. Near it was the Almozara, a flat area for military exercises, and next to it a spring water, which in Christian times was baptized as the Fountain of the Almozara. Today it is better known as the Fountain of Bañera.

At this time, Ejea’s importance lay more in the strategic aspect than in the socio-economic or demographic. Ejea was the most northern Muslim settlement with respect to the Christian centers of resistance in the Pyrenees. The interest that the Christian kings showed for Ejea was early. In the years 907-908, the Pamplona king Sancho Garcés I already wanted to take it away from the Muslims. In 1091, Sancho Ramírez tried again without success. But in 1105 the Muslims of Siya couldn’t withstand the thrust of King Alfonso I the Battler. That year the Christians conquered it definitively: from Muslim Siya it became the Christian Exea. For the conquest of Siya, Alfonso I had to combine Aragonese troops and surely, Pamplona and ultra-Pyrenean troops from Bigorra and the Languedoc. The first tenant appointed by the king of the Christian Exea was Lope López.

Five years after its conquest, Alfonso I the Battler granted Exea its Population Charter. It was the year 1110. It was a legal instrument through which the territorial limits were established and a series of legal norms were arbitrated for the new settlers. It must be said that there weren’t Muslims left in the lands of Ejea and that the king of Aragon was trying to attract new settlers, especially at a time when the Almoravids were pressing against the Kingdom of Aragon. In the Population Charter, the king granted numerous advantages to the inhabitants of Exea: they had the right to plow as many lands as they wanted, and after a year and a day, lands and houses would remain the property of the occupier; the merinos of the king (royal official, in charge of collecting taxes and exercising justice) couldn’t act in Ejea ; the Ejeans and their properties (houses and lands) would be fully free, they wouldn’t be subject to a feudal lord nor they would have to pay stately rents and they would obtain different judicial advantages.

The Ejean Population Charter was complemented with other provisions that ended up completing the set of privileges of the town. In 1124 the king granted Ejea full right over the waters of the Arbas and the possibility of creating ditches or dams. And in 1134 Ramiro II endowed the population with the La Penella salt mine.

In exchange for all this, the Ejeans were obliged to maintain a permanent military force, ready to defend the town. Two categories were established: knights and pawns; knights received twice as much land as pawns and in better places. With these provisions, the monarch gives the status of infanzonia to the Ejeans, equating them with the nobility, since in those centuries personal freedom and the exercise of war were distinctive features of the hidalgos.

In addition to the Christian settlers, Exea was nourished by the arrival of the Jews, a very important town in the history of the Crown of Aragon. The Jews had many privileges, which were directly supervised by the king of Aragon. The news about Ejean Jews is abundant. For example, in 1208, Pedro II of Aragón granted them the Castle of Ortes and the adjacent spaces with the intention that they would populate them, all of them in the La Corona neighborhood.

The provisions of the Ejea Population Charter had such notoriety that they generated a type of forality and its own legislation in the Kingdom of Aragon: The Charters of Ejea. These were applied to other populations and groups of people, sometimes with the same intention of maintaining a force armed in a border area or as a grant of personal freedom.

The space that the new Christian and Jewish settlers occupied on the territory was the old area of the Muslim Siya, located in the current neighborhood of La Corona. It is, therefore, in this medieval period when the development of its urbanism takes place and where Ejea takes on its nature as an urban space. In the center-east vertex of La Corona a walled enclosure was established that was reused by the Muslim zuda. In this enclosure the Abbey was established, headquarters of the French monks of Selva Mayor, who were in charge of Christianizing and collecting tithes. Next to the Abbey was the church of Saint John, the first Christian building after the conquest, which was reoccupied by the previous mosque. Around this defensive-religious space, the Muslim hamlet began to be reoccupied and a new one was built.

The construction of the church of Saint Mary, which was consecrated in 1174, is the border element of the first Christian demographic and urban expansion, since it was located in the western area of La Corona. This moment coincides with the construction of the first medieval Christian wall, which ran around the southern contour of La Corona, from Cantamora Street to Tower of the Queen, passing through The Carasoles and Tajada Street. Within this first defensive ring, next to the houses of the Ejeans, would be the Jewish quarter, the royal palace of Jaime II, the cemetery around the church of Saint John first and the church of Saint Mary later and the Tower of the Queen, embedded in the wall itself. This first wall had an entrance through three gates and was closed to the north by a huge natural precipice, which falls over the Arba of Luesia river and is now called Saint Gregory Quarry.

The population increase that Ejea experienced in the first half of the 13th century urged the settlers to build houses outside the first wall and to spread the hamlet to the south, towards the flat land. There was already a Mozarabic neighborhood outside the walls, so it isn’t surprising that the construction to the east of the church of Saint Salvador, consecrated in 1222, was in its vicinity. The hermitage of the Virgin de la Oliva to the west closed the perimeter of this moment of expansion.

A second wall was drawn later, then following the current line that marks the Paseo del Muro. The Zaragoza gate, next to the San Salvador church, the access gate to the Plaza (now Spain Square) through Toril street and the Huesca gate, at the beginning of the Huesca neighborhood (today Ramón y Cajal street) were the entry points to this urban layout.

Outside of the medieval urban case, there were various hermitages: Saint Matías, Saint Sebastián, Saint Peter…. The rest were orchards next to the Arbas, cereal fields in the dry land and mountains for sheep and forestry. And in the background, the great natural area of La Bardena.

During medieval times Ejea was the protagonist of important events. In 1265, Jaime I the Conqueror called The Court here, in which he finished modeling the figure of the Chief Justice of Aragon, who had to settle disputes between the monarchy and the nobility. Today, the figure of Justice is included in the Statute of Autonomy of Aragon as the defender of the rights of all Aragonese.

The kings of Aragon, from Alfonso I, were giving and confirming the privileges and privileges of Ejea: rights over the exploitation of river waters, tax exemptions, the right to climb, the privilege of childhood, etc.

The Late Middle Ages includes two key moments for Ejea and for the Ejeans: the support for the Unionists in their dispute with King Peter IV of Aragon (1348) and the definitive incorporation into the Crown of Aragon, in addition to the right to childhood granted by Alfonso V (1428).

MODERN HISTORY

The town of Ejea de los Caballeros emerged from the late Middle Ages, strengthened, protected by the king, all its privileges confirmed and positioned as a strategic enclave for the Crown of Aragon. The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were times of growth for Ejea, although he always had to fight against a hostile and harsh natural environment. Land, water and defense of their royal privileges were the axes that structured the life of the town at this time. But Ejea didn’t imagine that this glorious and hopeful start to the era would turn tragic and frustrating at the end of the Modern Age, in the 18th century. A war, a dynastic change and an epidemic changed everything.

In a transit of three centuries Ejea de los Caballeros went from the splendor of the town protected by the Crown of Aragon for two hundred years (16th and 17th centuries) to the gloom of disease and political ostracism in the 18th. It was a period that, like everything in life, had lights and shadows. It was a time in which the development of Ejea was directly and indirectly linked to the History of Spain, and to that of Aragon within Spain.

During the 16th to the 18th centuries Ejea de los Caballeros lived through a period of socioeconomic splendor, a boom in its artistic heritage and political consolidation as one of the most important population centers in Aragon. Being a royal town, configuring the Ejeans as free men, having consolidated privileges and having immense extensions of communal forest provided it with very useful tools to experience a complete development.

All this allowed urban growth, which expanded the settlement of the population from La Corona to the south, spreading down the hill towards the flat land, towards what is now the Paseo del Muro. The 16th and 17th centuries were a time when Ejea’s main palace-houses (in typical Aragonese style) were built, especially on the Mediavilla street- Spain Square- The Huesca neighborhood street (today Ramón y Cajal street).

It was a time when religious buildings were erected (Convent of the Capuchins, convent of the nuns of the Third Order of Saint Francisco and west portal of the church of Saint Mary); where a lot of civil work was promoted (reconstruction of the Saint Francisco Bridge, construction of the public fountains of Rivas and Farasdués, construction of the stairs to the Square); and where progress was made in spaces for education (Study of Grammar and Dialectics). In 1545, the Archbishop of Zaragoza, Hernando de Aragón, ordered the opening of chapels in the church of Saint Salvador, many of them paid for by wealthy families from Ejea.

The fact of being one of the most important towns in Aragon is confirmed by the fact that King Carlos I visited Ejea in 1527, reaffirming all his privileges and the right of infanzonia. The defense of their Privileges was a constant for Ejea and the Ejeans. A good example of this is the so-called Red Book, which compiles the royal privileges of the town of Ejea from 1110 to 1585, which were confirmed by Carlos III in 1767.

The municipal organization of Ejea was made explicit in the “Royal Ordinations of the Villa de Exea of 1688”, a compendium of norms that regulated both the operation of the town hall and the activities of the Ejeans. The festivities, the ordering of crops, the internal organization of the town hall or the operation of livestock were some of the aspects collected in the Ordinations.

But Ejea didn’t imagine that this glorious transition of the 16th and 17th centuries would turn into tragic and frustrating at the end of the Modern Age, especially in a disastrous century, the 18th, which began with the War of Succession and ended with the epidemic of The vote.

In the War of Succession (1701-1713), the town of Ejea ran, for different reasons, alongside the pretender of the Habsburgs, Archduke Carlos de Habsburgo. This support wasn’t free for Ejea. Felipe V, the Bourbon opponent, through the troops commanded by the Marquis of Saluzo entered Ejea on December 19 th 1706, causing the destruction of lives (240 dead), homes (152), heritage (walls, Convent of the Capuchins) and harvests (64 yoke of plowing). This fact caused a deep demographic, social and economic crisis in Ejea. She was joined by the humiliation of being snatched from the Capital of the Jurisdiction of the Cinco Villas, which Felipe V gave to Sos del Rey Católico as a reward for his loyalty. In addition, all Aragonese Charters and institutions were abolished, assimilating the administrative system to Castile.

The demographic, economic, social and patrimonial consequences of the War of Succession were very serious. A good part of the 18th century was characterized by the struggle of the Ejeans to regain the vigor of a town that had been severely punished. To this must be added a natural environment that is also very hostile, with inclement weather, natural disasters, poor harvests, food shortages and periodic diseases. This panorama accompanied the Ejeans for much of the 18th century and generated a constant climate of crisis.

When Ejea began to recover from the setback caused by the consequences of the War of Succession, an infectious contagious epidemic occurred between 1771 and 1773, which caused 335 deaths (most of them children) and the collapse of the Ejean economy and society. This epidemic, which was ended according to the tradition and belief of those Ejeans by the mediation of the Immaculate Conception of Mary, generated the festival of El Voto, which is still celebrated today in Ejea de los Caballeros every January 14 as an official local festival.

During the Modern Age, the main economic activity of Ejea de los Caballeros was sheep farming. Sheep and lamb cattle were part of Ejea’s agrarian landscape at this time. This sheep farming had two different exploitation models in time.

In the 16th and 17th centuries sheep farming based on transhumance predominated. From the Pyrenean valleys of Roncal, Salazar, Ansó and Hecho, the first two Navarrese and the second Aragonese, the flocks of sheep descended during the winter to the plains of Las Bardenas of Ejea and Corralizas de Propios, to return in summer to the cool mountain pastures. The existence of this transhumant cattle system generated the presence in Ejea of important Navarrese owners and of the north of the Cinco Villas. Even one of the most important gullies or cabañeras in Ejea was called “de los roncaleses”.

But from the middle of the 18th century onwards, the transhumant cattle ranching declined in favor of the expansion of an Ejea’s own cabin, which no longer moved from the municipality throughout the year. At the end of the 18th century, 75% of the cattle were shelves in Ejea, while 25% were still transhumant. And most of the owners were already local, local residents of the town, and not outsiders, as had happened in previous centuries.

There was also an important House of Cattlemen, which organized the operation of the cattle, articulated the power of the large landowners and defended their interests, especially against the Ejea City Council, owner of the main pastures.

Along with sheep, the breeding of wild cattle also stood out, especially during the 18th century. The wide plains of Ejea were the perfect accommodation for these herds of bulls and cows that soon achieved fame in the Spanish bullrings. Many of those bulls were fought by Antonio Ebassun, better known as Martincho, the bullfighter who was born in Farasdués and settled in Ejea was immortalized by Francisco de Goya.

The extensive plains of Ejea and the existence of a very wide communal mountain, inheritance of the condition of town of Realengo, propitiated the development of a rainfed agriculture dedicated to the “Mediterranean triad”: wheat, vine and olive tree, in this order. This agriculture was very weak, as it depended a lot on the weather conditions. At this time, little more than 5% of Ejea’s term was cultivated, a minimum extension taking into account the extent of the term (615 km2).

A constant of the people who populated Ejea de los Caballeros was the regulation of water, a very rare commodity in these parts. That obsession already starts from the 18th century. In 1768, an infantry captain named Juan Mariano Monroy presented Carlos III with a project that was perhaps economically unviable at that time, but revealing of what happened many years later, in the 20th century. This Monroy project aimed to build an irrigation canal that, starting from the Aragon River, and after irrigating the plain of the Cinco Villas, would reach a total of 15,263 hectares. It was the germ of the Canal de las Bardenas, which saw the light in 1959.

CONTEMPORARY HISTORY

Ejea enters the Contemporary Age being the scene of the struggles of the change towards a liberal society, which manifests itself especially in the 19th century, while the contradictions and deficiencies of this new system will give rise to political movements and demands, which will be expressed in Ejea with greater force in the 20th century. Land, as the municipality’s basic resource, will be the axis around which the social and economic transformations will revolve, as well as the attempts at modernization, which will seek to break through the inertia and immobility typical of the rura lAragonese environment. Communications and irrigation, two centers of interest and demand for progress-loving of Ejea, have marked and continue to guide the agenda of future challenges for the municipality of Ejea and its region.

The War of Independence (1808-1814) was the first of the convulsions of the crisis years of the Old Regime. June 1st 1808, the City Council and the Junta were convened, and mass and prayers were celebrated for the victory over the French. The next day men between 16 and 40 years old were called to enlistment, joining the anti-French uprising. The Ejea City Council sent a representation to Zaragoza to express the enthusiasm of the people and ask for a vote in the newly convened Court. Of the little more than 2,000 inhabitants of Ejea, 250 left for Zaragoza, although some abandoned on the way. Other Ejeans demonstrated their bravery in resisting the French invader, such as Juliana Larena Fenollé, declared a heroine in the defense of Zaragoza during the Sieges by General Palafox.

Throughout the war in Ejea de los Caballeros there were several clashes with French troops, with moments of harsh repression. The war depleted agriculture and livestock, leaving a town devastated and subjected to taxes that were collected with great harshness. Also, during the Carlist wars, Ejea suffered the consequences of the near threat of Navarrese Carlism, with repeated looting and great losses.

After the defeat of the French in the War of Independence, the situation in Ejea’s lands returned to normal. The Restoration, with the regency of Queen María Cristina returned to relocate Ejea internally. In addition, in 1834, the judicial district of Ejea de los Caballeros was created, which articulated the central-south of the Cinco Villas.

With the liberal agrarian reform, the land privatization process began. The confiscation of Madoz in 1855 imposed the sale of their own assets. The city council of Ejea kept its commons (some 10,000 hectares excepted from public auction) and sold half of its pens to the rich local or Pyrenean cattlemen and to Zaragoza bourgeoisie, who accumulated large extensions.

To this were added the arbitrary breaking of the communal, later legitimized, and the usurpation of land by inscription in the property registry. In the middle of the 19th century, with all this, a massive process of putting municipal lands under cultivation began, which gave rise to an extensive and practically uniform dry-land cereal landscape.

In Ejea, in the first two decades of the twentieth century there was an increase in the land clearing process, which was driven by political events, such as the neutrality of Spain in World War I (1914-1918) that arbitrated him as supplier of cereal to the contending countries. Of the 5,376 hectares plowed in the communal in 1906, it went to 11,605 in 1920. This growth in the cultivated area led to an increase in the number of peasants, from 709 to 1,337 in the same period, which led to the increase demographic and the weight of agricultural activity in the economy of Ejea.

At the beginning of the 20th century, technical advances such as the bravant plow, chemical fertilizers and mechanization were joined to the birth of the large areas of cultivation, giving way to a cereal-based agricultural specialization that generated wealth in the area and increased agricultural production. Ejea was a pioneer in the importation of agricultural machinery, accompanied by exhibitions and demonstrations of machines such as combines, threshers and tractors. The local workshops specialized in the repair of this machinery, later they became representatives or branches of large firms for its commercialization, and, over time, into top-level manufacturing companies on a national scale. This strength of agricultural machinery manufacturing companies persists today, in the XXI century.

The starting up of the Sádaba-Ejea-Gallur train in 1915 allowed the export of agricultural surpluses, until then made difficult by isolation due to the almost nonexistence and poor condition of the roads. It favored the output of cereals and beets, and the arrival of mineral fertilizers, being an engine of development for agriculture and the economy of the area. It stopped working in 1970, when it lost profitability because it was narrow gauge and couldn’t compete with trucks. The train station was a key piece in the urban planning of the Expansion district and the municipal slaughterhouse and the cereal granary were built in its surroundings.

All this, together with the birth of the flour industries and the use of agricultural machinery, led to a modernization stage in Ejea at the beginning of the century. Linked to agricultural growth, there was a population increase, mainly led by the immigration of people from the environment and, already in the 1920s, Ejea consolidated its demographic primacy in the region.

The proclamation of the Second Republic in Ejea on April 14, 1931 gave way to a stage of great political and social effervescence. In the municipal elections of 1931 he won the Republican-Socialist candidacy, which was a great novelty in the local political panorama.

With the Second Republic, a broad program of social and economic reforms was launched in Ejea. Among them, the recovery for the municipality of the lands of the Ejea communal usurped by some landowners and the plowing of communal lands stood out, so alleviating the hardships of an important mass of peasants. Other issues that concerned the Ejea’s city council were infrastructure and improved communications, with the construction of roads. A hope that was expected to be near was the arrival of irrigation to the dry lands, with the beginning of the works on the Canal de las Bardenas in 1933.

In Ejea, in 1932 the Girls’ School was inaugurated and in 1933 the first school in the La Llana neighborhood. In 1936 the construction of the Children’s School was awarded and the republican city council was involved in obtaining a Second Education center for the town, offering for its installation the second floor of the town hall that was inaugurated in 1931.

After the Civil War, the Franco period began. Starting in 1959, with the technocratic governments, a period of strong economic growth began, with new guidelines for opening up to the market and surrounding countries. In Ejea, that 1959 was a special year, which meant the inauguration of the Canal de las Bardenas for the local recovery. Despite the large agricultural area of the municipality, the lack of water and irregular rainfall made the annual harvest uncertain and generated an enormously fluctuating and vulnerable economy.

In 1879 the City Council of Ejea had already inaugurated the Saint Bartolomé reservoir, expanding the traditional irrigation systems. Different projects proposed over time the use of the waters of the Aragon River to irrigate the plains of Ejea. The Yesa reservoir construction project, approved in 1926, should allow the necessary water to be stored. The construction of the Canal de las Bardenas was projected earlier, in 1924, but the works began in 1933 and came to a halt with the Civil War, finally opening the first section of the canal in April 1959. The long process thus culminated in the arrival of the water to Ejea, which had to go through various political stages, with the approval of the Canal de las Bardenas project in the reign of Alfonso XIII, the beginning of the works in the Second Republic under the government of Manuel Azaña and its official inauguration with the visit to Ejea by Francisco Franco.

The irrigation of thousands of hectares led to the construction by the National Institute of Colonization of six new villages. The first three, Bardenas, El Bayo and Santa Anastasia, would be followed by Pinsoro, Valareña and El Sabinar, regularly distributed over the new area of the municipality of Ejea, irrigated by the Canal de las Bardenas. These new settlements were added to the historical nucleus of Rivas and, with the incorporation of Farasdués in 1973, they complete the eight towns that together with the town of Ejea make up its municipal term today.

The arrival of the railroad (1915) and the inauguration of the Canal de las Bardenas (1959) were two milestones of the 20th century that boosted the economy and urban development of Ejea de los Caballeros. From then, the urban area of Ejea was expanded with the expansion district, following an orderly model of an urban plan that has given rise, over the years, to a sustainable growth of the city’s planning.

All this historical transit has reached our days, and today Ejea de los Caballeros is one of the main municipalities of Aragon. A place where people always open arms to welcome those who come from outside.

(*) This historical review is fed by a summary of the book Historia de Ejea, whose authors are Carmen Marín, Elena Piedrafita, José Luis Jericó, José Antonio Remón and Marcelino Cortés.